Scene-setting, eye-opener

Saturday evening. You walk into a mall carrying a “Nayuki の Tea”. Straight ahead you spot “Nalei の Tea”. Same colour scheme, same cup curve, even the staff caps feel familiar—only the Chinese character “lei” differs. You freeze for three seconds; your best friend whispers, “Is this a Nayuki sub-line?”

Congratulations—you have just experienced what the law calls “initial-interest confusion”.

Our just-released 2025 Brand-Confusion Cognition Survey shows:

-

72 % of shoppers have mistaken a knock-off for a “sibling brand”.

-

Barely 21 % can nail the fake at first glance.

-

Only 7 % bother to read the wording on the trademark.

In short: what meets the eye may not be true, yet courts keep asking “what did the eye see?”

I. The yard-stick of infringement—likelihood of confusion

Article 57(2) of China’s Trademark Law is terse: “Using, on identical or similar goods, a mark similar to the registered trademark, which is likely to cause confusion” equals infringement.

The keyword is “confusion”, but confusion lives in the mind. How do you measure a feeling? Judges, lawyers and researchers have split the abstraction into five concrete indices:

-

Similarity of marks (sound, look, meaning)

-

Similarity of goods/services

-

Distinctiveness of the earlier mark

-

Level of attention of the relevant public

-

Evidence of actual confusion (wrong orders, customer hotline complaints, social buzz)

No. 4—“level of attention”—is the slipperiest. The judge wants to know: “How carefully do your consumers actually look?” That is where a market survey becomes a vernier caliper, gauging “how alike is alike”.

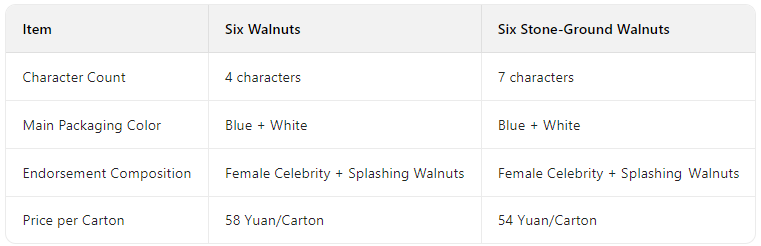

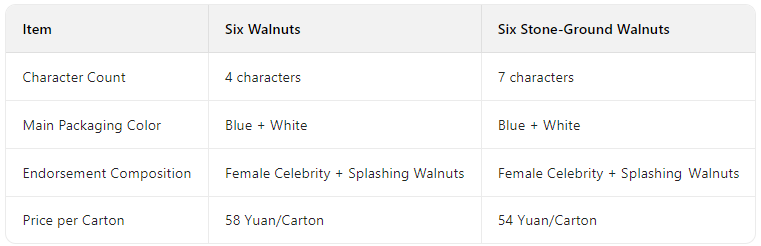

II. A textbook crash—“Six Walnuts” v. “Six Stone-mill Walnuts”

The Supreme Court’s 2023 final decision:

-

“Stone-mill” merely describes a process and lacks distinctiveness;

-

The overall rhythmic core is still “six + walnuts”;

-

Combined with blue-white packaging and beverage category, “the relevant public is likely to err” → infringement confirmed, damages RMB 12 million.

Survey bonus: we showed un-branded pack shots on a Shijiazhuang street; 68 % pointed at “Six Stone-mill Walnuts” and said, “This is the new Six Walnuts”—a numeric footnote to “confusion”.

III. How careless are shoppers?—an experimental lens

Design

-

Sample: n = 1,006 beverage buyers, tier-1 to tier-4 cities, aged 18-55.

-

Double-blind mock shelf: 12 genuine or knock-off products randomly placed, 10-second choice window.

-

Eye-tracker logged first fixation and dwell time.

Findings

-

Average gaze time: genuine 1.2 s, knock-off 1.1 s—indistinguishable at a glance.

-

Text area fixated < 0.4 s; colour + graphic area > 1.0 s.

-

Post-purchase “confidence” score: shoppers who picked wrong were more confident (7.3/10)—the fake bred visual over-confidence.

Take-away: “alike” or “not alike” is decided by colour blocks within one second, not by reading. One courtroom photo of a mis-purchasing consumer beats ten pages of legal theory.

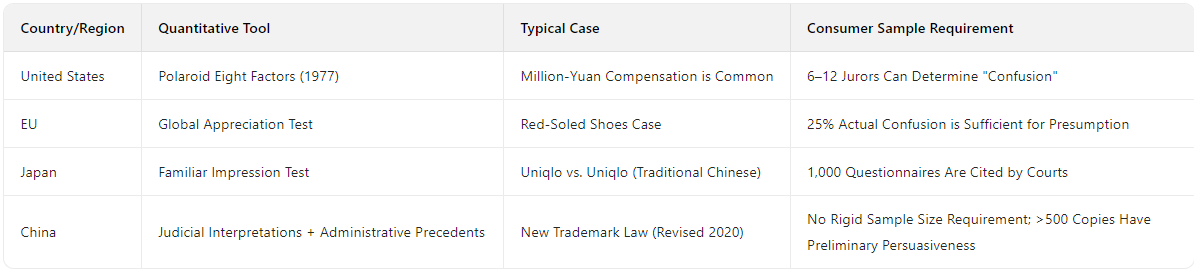

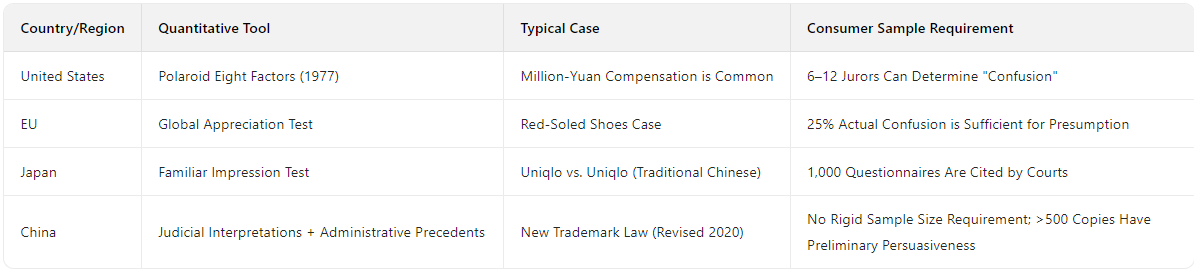

IV. Global comparison: measuring the world’s “alike-ometer”

V. Upgraded survey tech: from “asking” to “traces”

1.E-commerce mis-purchase logs

Pull 30-day backend data: search keyword “Nayuki” → click “Nalei の Tea” → refund rate 19 %, five times the industry norm. Mis-click rate = hard index of actual confusion.

2.Call-centre text mining

“Did I buy the genuine one?” “Why does it taste different?”—frequency > 20 per 1,000 calls can establish “actual confusion”.

3.Social-media semantic drift

Under the Nayuki翻车 (fail) thread, 18 % of users @-ed the official account asking “Did you change packaging?”—evidence of goodwill impairment.

VI. Three Swiss-army knives for counsel, legal affairs and brand owners

1.Prevention: make distinctiveness a visual hammer

Don’t let wording carry recognition alone. Unique bottle shape, exclusive Pantone, animated QR code all raise differentiation and cut “alikeness” risk.

2.Evidence collection: freeze market confusion in real time

Spot a knock-off? Place a notarised order and launch a rapid micro-survey (report in 48 h) to underpin a preliminary injunction with “irreparable harm”.

3.Litigation: swap “feeling statements” for a “cognition curve”

Compress questionnaires, eye-tracking and mis-purchase data into five visual pages that let a judge grasp “how alike” within three minutes—far better than adjectives.

VII. Future borderlines of “alike”

-

In the metaverse, will virtual goods use the same confusion ruler?

-

If an AI-generated logo “colour-clashes” with a registered mark, who is liable?

-

How do you measure “alikeness” for olfactory or tactile marks (scented sneakers, touch-feel packaging)?

The list grows, but the core stays—ask consumers first, then ask the judge.

Conclusion

“Alike” versus “not alike” is never a designer’s pixel game; it is a three-dimensional tug-of-war among psychology, law and the marketplace. Whoever can turn “what first flashes in a shopper’s brain” into evidence the court accepts holds the offensive and defensive trump card in an infringement battle.

Final pop quiz—

Which cup below is the knock-off?

A. Heytea

B. Hecha

C. Hicha

Leave your answer; your one-second hunch might decide the next courtroom second.

Trademark infringement Consumer cognition